How COVID-19 could impact the most vulnerable in L.A. County

The COVID-19 pandemic may disproportionately impact the most vulnerable communities in Los Angeles County, reveals analysis by the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity (PERE) at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

Marginalized segments of the population, including low-income seniors, undocumented immigrants, and rent burdened families, face substantial inequities that will affect how well they weather the pandemic.

Identifying those most at risk helps the entire population avoid the spread of disease and could lessen disastrous economic fallout, which would only worsen existing inequality, the PERE report argues.

Seniors teeter on the edge

Many seniors—including more than 30% of black, white and Native American seniors—in L.A. live alone, which makes them more susceptible to isolation and a lack of information about the virus. Without support from local family, they may have to grocery shop and pick up medications for themselves, despite the high risk that going out in public presents to the elderly.

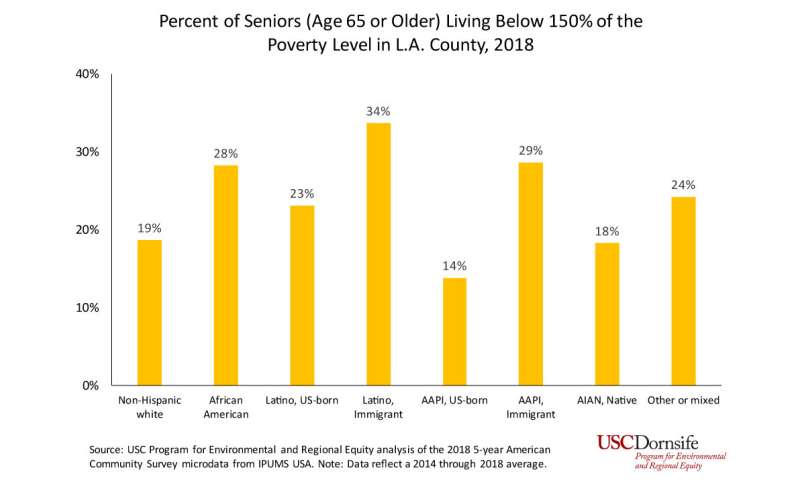

Additionally, many seniors are living on limited incomes, particularly people of color. Almost 35% of senior Latino immigrants, and nearly 30% of African American and Asian American and Pacific Islander immigrants live near or below the federal poverty level. The costs of contracting the illness could be devastating for those with few economic resources.

Certain neighborhoods, such as South L.A., have larger numbers of seniors experiencing financial insecurity, with nearly 40% living near or below the federal poverty level.

Undocumented workers at the frontlines

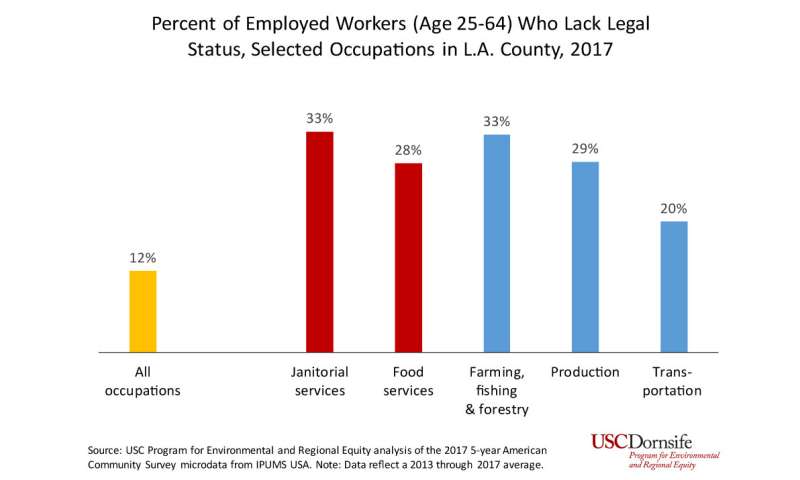

Undocumented immigrants—which includes 12% of L.A. County’s workforce—are also disproportionately at risk. They are often employed as janitors or farm laborers, positions that can’t be suspended during the pandemic and that place them at the frontline of exposure. Many also work in industries hard-hit by a slump in demand, such as food service, where 28% of workers are undocumented. Shuttered bars and restaurants mean no paycheck, along with no unemployment coverage due to the lack of workplace protections for undocumented workers.

Nearly 1 in 5 L.A. County residents are either undocumented or live with a family member who is, which means that the children and relatives of these workers will also be affected. Those still working could potentially bring the disease home to family members.

Paying rent or buying groceries may no longer be feasible with the loss of an income and publicly funded financial relief is not an option for this group. Undocumented workers have been excluded from receiving stimulus checks under the COVID-19 relief package, even as their tax money contributes to the fund.

Many lawful permanent residents work in these same industries. Some may be fearful of tapping into supportive government resources, such as unemployment insurance or COVID-19 testing, out of concern they’ll be considered a “public charge” and derail their naturalization process. United States Citizenship and Immigration Services has already indicated that testing and treatment for the virus would not count in the determination of public charge, but anxiety persists.

The digital, language and transportation divides

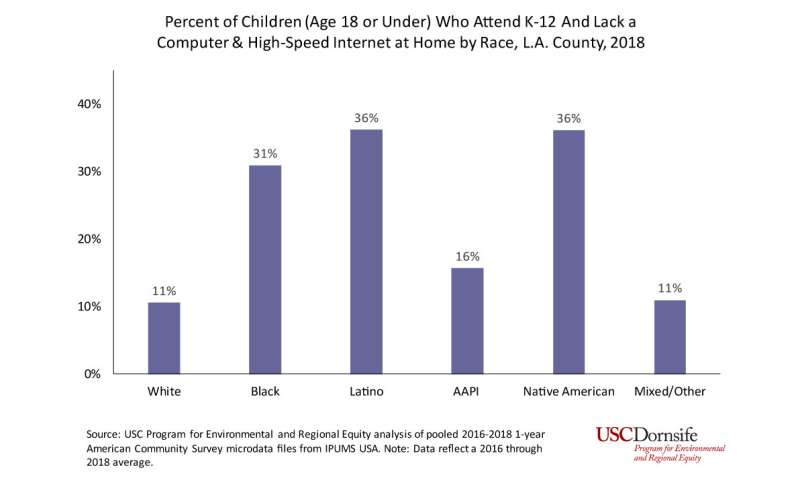

Across L.A. County, school districts have shut their classrooms and sent children home for home-based instruction. Unfortunately, not all children have access to the same resources, particularly along the lines of race. About one in three black, Latino and Native American children attending K-12 schools lack a computer and high-speed internet at home, essential to effective online learning.

For many households in the county—including more than one-quarter of households in Southeast L.A. County—no one age 14 or older has a strong command of spoken English. They could miss crucial information on the pandemic if translation of public announcements is not available. Those unaware of safety measures may inadvertently expose themselves—and others—to disease.

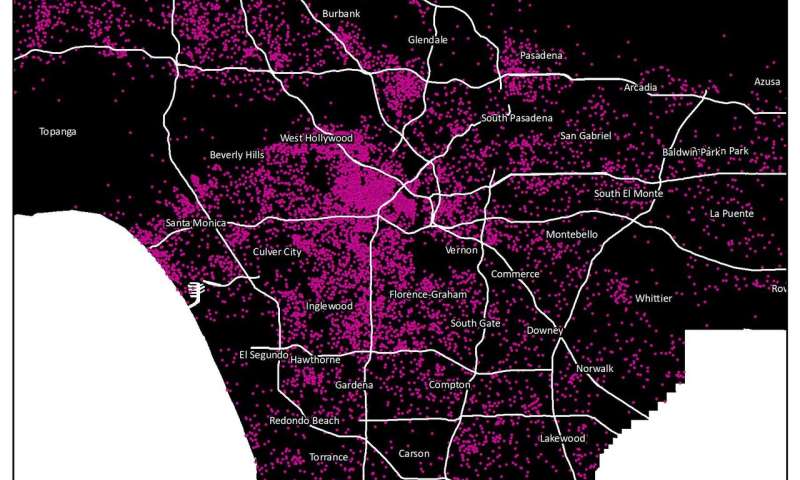

Households in L.A. without a car often rely on public transit. This heightens the risk of exposure for those sharing train cars and buses. As the pandemic worsens, transit service may be disrupted, which leaves many unable to get to the store or to work. Carless households are particularly concentrated in Hollywood, Koreatown, mid-City and South L.A., which makes residents of entire neighborhoods more vulnerable to disease transmission and isolated from services.

A rental crisis

As workers continue to stay home from work or lose their jobs, renters may have trouble keeping a roof over their head. More than half of renters in L.A. County experience rent burden, defined as paying at least 30% of income on rent and utilities. With the possibility of a months-long shelter-in-place policy, paying rent for the foreseeable future could be an impossibility for thousands of people across the county.

Source: Read Full Article