Shedding new light on the origin of metastases

Before an effective treatment can be devised, researchers have to understand the specific effect of an anti-cancer substance on the cell type, or even the cell, that produces metastases in the enormous cellular heterogeneity of tumors. A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) used a pioneering technique called spiked-scRNAseq that links the transcriptomic to single cell metastatic phenotypes of colon cancer tumor cells. The importance of the VSIG1 gene involved in intercellular interactions has been identified: It prevents metastases. In addition to this discovery—which offers hope for developing future treatments—the article published in Cell Reports validates the use of this technology for testing drugs that are active against metastases, including for personalized approaches.

Most drug treatments for cancer do not work optimally against metastases. In fact, they have been developed to have a global action and the greatest possible effect on the average patient. To be effective, says Professor Ariel Ruiz i Altaba at UNIGE’s Faculty of Medicine, “drugs should be targeted only to cells that generate metastases.”

Tumors are made up of cells that are very heterogeneous, some of which will produce metastases while others will not. The question is how to target the right type of tumor cell as a means to beat cancer.

The team led by Professor Ruiz i Altaba set up a methodology for defining the cellular phenotypes for tumors, as well as cloning and tracing them, using a cell-scale analysis of both the genome and the resulting mRNA expression. The genes of a cell, or its genotype, are first copied into messenger RNA, which is then often used for protein synthesis. These proteins are the visible expression of genes, and their action underlies measurable characteristics of the cell, i.e., its phenotype. “Our approach means it’s possible to identify the missing pieces of the tumor puzzle by linking the expressed genotype to the cellular phenotype. In essence, we want to know how cells become metastatic and where they come from.”

Model Validation

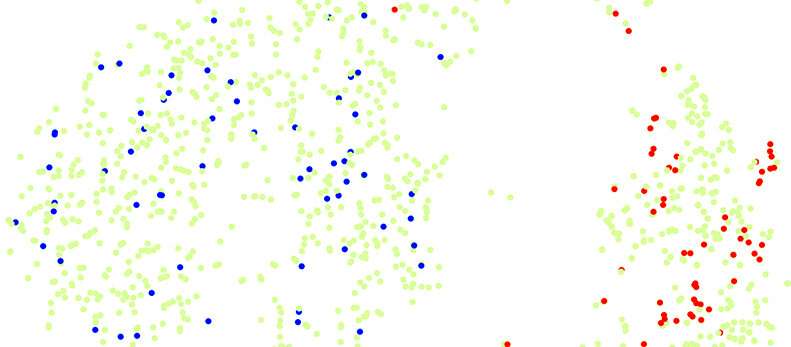

By developing and using the spiked-scRNAseq technique, which combines omic approaches and phenotype determination of single cells that are then “spiked” into the original heterogeneous cell population, the researchers succeeded in precisely defining the composition of the tumor populations while determining their phenotype at the cellular level.

To do this, they first genetically labeled several types of tumor cell so they could observe their metastatic behavior. Once the phenotype was known, cells of the same clone were “spiked” into the heterogeneous colon cancer primary cell population and subjected to single cell sequencing. The molecular profile of cells with metastatic potential was thus identified by the homing of spiked metastatic cells to a specific cell group or cluster.

Based on this approach, drugs and their anti-metastatic effects could be precisely tested. “In other words, we can use this approach to analyze compounds for their action on the cells that generate metastasis in individual patients,” explains Dr. Marianna Silvano, a postdoctoral fellow at UNIGE and co-first author of the study.

Identifying a Metastasis Suppressor Gene

The researchers then applied this approach to understanding tumor behavior. “We set about defining the pre-metastatic status of a tumor and assessing its metastatic potential,” continues Dr. Silvano. The Geneva research team discovered that by mixing cells that have a metastatic phenotype with non-metastatic cells, the former stopped the migration of the latter. “This indicates that restrictive cellular interactions are important in the process of metastasis formation,” explains Professor Ruiz i Altaba.

On the back of these results—and with genomic and transcriptomic analyses in hand—the research team focused on the genes involved in the signaling pathways that are important for cellular interactions. Dr. Carolina Bernal, a postdoctoral fellow and co-first author of the study, identified the VSIG1 gene and she and Dr. Silvano nailed it as critical of the restrictive interaction between non-metastatic and metastatic tumor cells.

Source: Read Full Article