Human mini-lungs grown in lab dishes are closest yet to real thing

Since the COVID-19 pandemic reached the United States in early 2020, scientists have struggled to find laboratory models of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the respiratory virus that causes COVID-19. Animal models fell short; attempts to grow adult human lungs have historically failed because not all of the cell types survived.

Undaunted, stem cell scientists, cell biologists, infectious disease experts and cardiothoracic surgeons at University of California San Diego School of Medicine teamed up to see if they could overcome multiple hurdles.

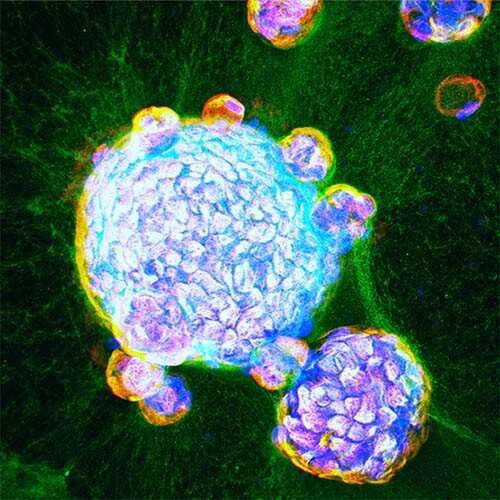

Writing in a paper publishing August 31, 2021 in eLife, the team describes the first adult human “lung-in-a-dish” models, also known as lung organoids that represent all cell types. They also report that SARS-CoV-2 infection of the lung organoids replicates real-world patient lung infections, and reveals the specialized roles various cell types play in infected lungs.

“This human disease model will now allow us to test drug efficacy and toxicity, and reject ineffective compounds early in the process, at ‘Phase 0,’ before human clinical trials begin,” said Pradipta Ghosh, MD, professor, director of the Institute for Network Medicine and executive director of the HUMANOID Center of Research Excellence (CoRE) at UC San Diego School of Medicine. Ghosh co-led the study with Soumita Das, Ph.D., associate professor of pathology at UC San Diego School of Medicine and founding co-director and chief scientific officer of HUMANOID CoRE.

Stem cell scientists at the HUMANOID CoRE, led by Das, reproducibly developed three lung organoid lines from adult stem cells derived from human lungs that had been surgically removed due to lung cancer. With a special cocktail of growth factors, they were able to maintain cells that make up both the upper and lower airways of human lungs, including specialized alveolar cells known as AT2.

By infecting the lung organoids with SARS-CoV-2, the team discovered that the upper airway cells are critical for the virus to establish infection, while the lower airway cells are important for the immune response. Both cell types contribute to the overzealous immune response, sometimes called a cytokine storm that has been observed in severe cases of COVID-19.

A computational team led by Debashis Sahoo, Ph.D., assistant professor of pediatrics at UC San Diego School of Medicine and of computer science and engineering at Jacobs School of Engineering, validated the new lung organoids by comparing their gene expression patterns—which genes are “on” or “off”—to patterns reported in the lungs of patients who succumbed to the disease, and to those that they previously uncovered from databases of viral pandemic patient data.

Whether infected or not with SARS-CoV-2, the lung organoids behaved similar to real-world lungs. In head-to-head comparisons using the same yardstick (gene expression patterns), the researchers showed that their adult lung organoids replicated COVID-19 better than any other current lab model. Other models, for example fetal lung-derived organoids and models that rely only on upper airway cells, allowed robust viral infection, but failed to mount an immune response.

“Our lung organoids are now ready to use to explore the uncharted territory of COVID-19, including post-COVID complications, such as lung fibrosis,” Das said. “We have already begun to test drugs for their ability to control viral infection—from entry to replication to spread—the runaway immune response that is so often fatal, and lung fibrosis.”

Since their findings in human organoids are more likely to be relevant to human disease than findings in animal models or cell lines, the team hopes that successful drug candidates can be rapidly progressed to clinical trials.

Source: Read Full Article